Iryna Kupchynska

Iryna Kupchynska is a poet, essayist, and performer. Her texts have been published in Ukraine and Germany, she also stages poetry-music performances. She currently works as a memory work consultant for an international development agency in Ukraine.

About the Project

by Iryna Kupchynska

After I first arrived in Sarajevo, I could not take my eyes off the traces of shells and bullets on the city’s buildings. Once you learn about the Sarajevo roses, you cannot help but look for the red marks on the asphalt. Never mind the roused breathing of the urban space, full of commercial places and European fashion brands – my attention was drawn to these scars on the face of the revitalized and living city.

Was it my knowledge about the war that kept my attention glued to Sarajevo’s past, preventing me from embracing the everyday flow of people and places, the lymph that has since filled up the bumps and deficiencies, the traces and pits in the facades and pavements?

Does the war take over life or does life take over the war? Knowledge of the past influences our perception of the present, of course, but how exactly? Is this something we can avoid?

The present can never steer clear of the past. Everything is plagued by what was, by the infrastructure that gives shape to our lives and environments, built and created according to once-modern ideas about what is good, correct, and proper. The inescapable mold of previous lives is abundantly decorated with the tragedies of the past. Violence has shaped our geography, our borders, our cities, our very behavior. We hold out our hand in a greeting to show we carry no arms. We illuminate our streets to provide a feeling of safety. Armies persist in their attempts to scare off a possible adversary.

Still, you can forget about it, once you let your attention slip for long enough. Does the river think about the banks that direct it?

I am studying a couple of locations in Sarajevo in my “Narrative postcards”. The viscous reality of everyday life inhabiting spaces shaped by the past. I collect memories of other people and pair these with a random mosaic of historical events, then watch them merge into a picture of the flow of life. This is quite enjoyable once you slow down: everyday worries, petty conversations, mundane actions, all framed by nature itself, with its incessant renewal and glow of eternity.

Sarajevo is rich in memories, rich also with life. Could this be said about every place that ever lived, every place that suffered? Once your attention shifts to the stream of events, the nuances of life overshadow the pain of the past, even though the memories do invade the mundane, shape it, define it.

The city puts on a wide happy smile but its lip is bruised.

Photos Dzvinka Pinchuk

At Mejdan

A massive bearded guy on a scooter in red sneakers straightens his feet forward, as if to brake, but keeps driving, and turns onto the bridge. I am also turning onto the bridge, only on foot. The traffic is crazy, feels the same as Georgia, I wouldn’t dare to drive here.

She says that when she is stopped for violating traffic rules with her son in the car, they always let her go, melt, and say something nice. Everyone here is crazy about children. Many years of siege, and emigration. Every child is worth its weight in gold.

I think about the straightened legs of a motorcyclist. Does he have children? So easy to get into a pit, and break both legs, as easy as a walk in the park.

The seagull walks on the water. It does not land, it floats down. With feet in the water, it walks on a dam, allowing life to bring food by itself. Occasionally it dips its beak into the current of Miljacka and catches something. Several empty bottles are dangling near the buoys.

The grass in the park is still fresh, bright green in the unusual April heat. A young man gets up from the bench with two crutches and one leg. Above the park, I pass two black and white cats. Two women in black sweaters, white scarves and white sneakers are praying at the mosque fence.

It smells of the slow freshwater of the river, the occasional heavy perfume, the exhaust fumes of the nearby street.

The music pavilion at At Mejdan Square was built in 1911 by the Austro-Hungarians for the ladies and officers who came to the Sunday brass concerts. Now the music pavilion is a coffee shop. It gathers people around on green plastic styled as metal seats. The jazz is on. And obscenely loud birdsongs on, too. Sounds like blackbirds. A crow screams loudly near the river.

One and only waiter-and-barista, two in one, is running between the pavilion and the tables. Big drops of sweat are covering his forehead. A handsome man, he seems to barely breathe from running around. In the official Sarajevo guide, it is recommended to drink Bosnian coffee here; they have run out of it. Apparently, people are listening to the same audio guides. Bored, stupid tourists. Like me.

Franz Ferdinand was killed nearby, on the Latin Bridge. Many years of the First World War, men had some fun traveling in male company, dying suddenly though.

Near At Meydan, on the opposite side of the river, is the Ministry of Defence of Bosnia and Herzegovina. “Odbrane” – means “defence,” it sounds like “taken away, seized” in Ukrainian, but wasn’t it seized after the siege of Sarajevo? Five teenagers, all in blue jeans, are sitting on the steps opposite the park, smoking in the shade.

The Ministry is marked on Google Maps – I’m not revealing the secrets of the military infrastructure, don’t you even think I would do that! One can ask them questions, and people write; the Ministry, of course, does not answer them on the maps. Google automatically translates these cries into a digital nowhere of maps, preserving the punctuation marks:

– I need a certificate for my father that he was not in the war in order to receive a pension, I need to fill out the application and send you how long it will take to return

– Can someone explain to me how to write an OMO request for the 15 months spent in the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the period 1992-1993, since I do not have any documents

– Hello, I’m calling from Bihac, I urgently need a confirmation or a solution as to how long I was in the professional army after the war, I know I was there for about 6 years, but I need a solution since when and urgently, is there any way to get it

The sign says: “Danger of the facade collapsing”.

By the river, a middle-aged woman in a long skirt holds a white fluffy dog in her arms; she wipes his ass with a napkin.

Clinging to an electric block between tall, dense trees – only those trees that were in the line of the fire remained tall in Sarajevo, all the others were cut down for fuel during the siege – a black garbage bag happily shakes the remnants of rags, like a tattered centipede.

Joyful, overheated demon of Sarajevo.

Hotel Holiday

A tram passes the former sniper alley; a girl who is seductively drowning in popcorn pulls an exploded corn into her mouth. It’s an advertisement for “Cineplexx Sarajevo”.

Sarajevo is cinematic: near the hotel lobby, bullet and shell marks are embarrassingly hidden under the concrete. Journalists lived here during the siege: “It was stupid because every time we went out we were fired upon.” On the other side of the hotel is Cineplexx, with a view on the restored TV tower up the hill. “We had no communication: only a satellite phone in the presidential palace… No, war journalists’ work has not changed in 30 years. How did we survive? We had generators in the basement. Not everyone will tell about this: we went there,” – he points somewhere towards the parking lot behind the cinema, – “to the UN barracks to bribe Ukrainian peacekeepers. It was not difficult; we bought gasoline from them and it was enough for 2-3 hours of electricity per day. The most important ones were kettles and, later, also computers. We smoked a lot.”

Behind the cinema and hotel’s parking lot – is a hookah bar named “Inferno”. Near it is a flower bed painted with silver: an ancient village cart pulled by two horses, one quarter scale. After all these stories, this Inferno is only 25% – tops.

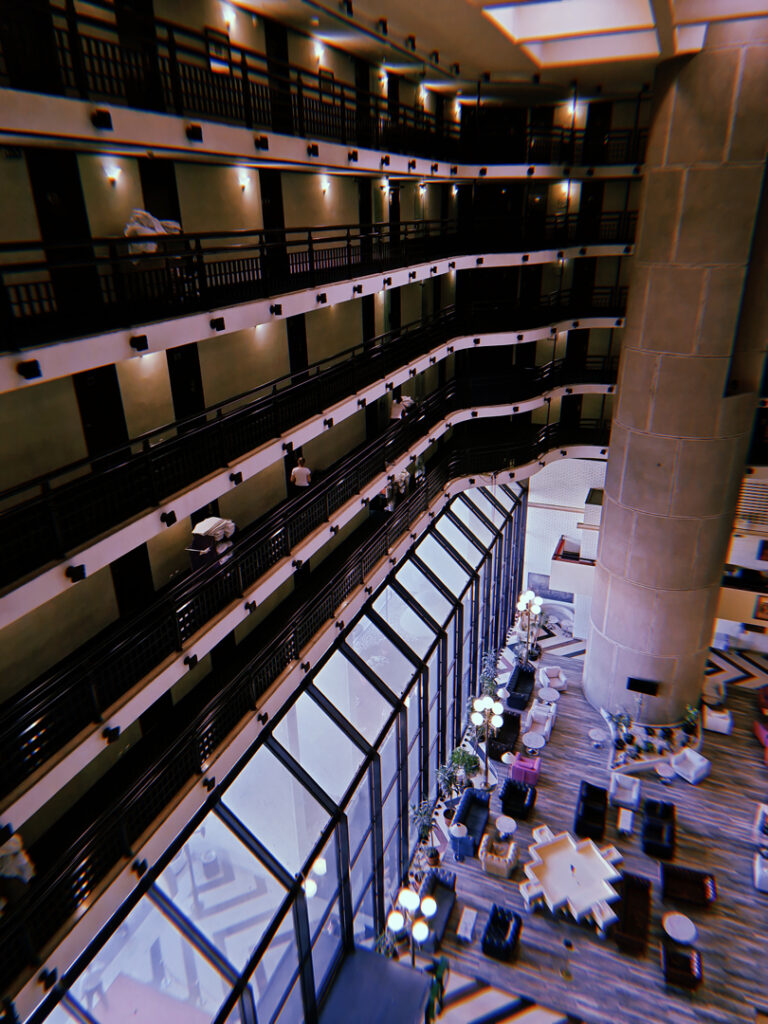

The hotel was opened in the 80s before the Sarajevo Olympic Games. I go inside and see the concentrical corridors of rooms around the giant lobby. “Foucault’s Panopticon,” I think. I think that I don’t like when people can see who enters my room and when they leave. Yet here everything is in full view. Damn Yugoslavian communists with a culture of surveillance.

A sundial at the top of a building shows around 11 o’clock. Under it, a couple of bricks are knocked out by bullets. Between the sundial house and the hotel – a kiosk with a painted Mexican man in a white shirt, red pants, and a green jacket. Next to it, the Palestinian flag of the same size, in the same style: red, white, green, and black.

A cherry tree blossoms; a silver birch dropped her earrings behind the hotel, a tree of easy virtue.

The sound of the freeway could be heard, disrupted by the fountain in front of the central entrance to the hotel. Birds are violently chirping above the blossoms. Two sparrows are fighting over cookies, too big for the bird.

Kronos, father of Zeus, god of the Time, squints with one eye of a sundial over the surrounding commotion. On gloomy days, the shadow of the gnomon does not descend. It is not known where the god of time directs his gaze. Perhaps, he goes to the other side of the hills to rest.

A good hotel: it has a swimming pool, breakfasts, stories. Looks like there are bedbug bites under my scars.

Vijećnica

City Hall / National Library

Two rows of columns of the city hall building are like sharpened teeth, built in a pseudo-Moorish style. The ceiling inside the hall breaks the heart and the sun into a hundred fragments of stained glass.

In the corridors, there are in a display kitschy, badly redrawn paintings from photographs from the time of the siege. They are with exaggerated contrast: children with weapons and adult faces with smeared eyes. Marble and stones, bright ornaments on the walls, with a couple pale ones in several places to show the preserved original patterns, from before the fire.

I glance into one of the halls, where a girl is not too eager to hug a man twice her age. She has a beautiful round face, a short white coat, and black tights. He has a neat bald patch on the top of his head, a grey sweater, and an old man’s shoulder bag. She awkwardly looks up at me from behind his shoulder. I decided to bypass the room. I see them later in the corridor. She keeps 30-50 centimetres away from him, stumbling from foot to foot.

Selma says:

– At the Town Hall? Oh, this is terrible, I try to avoid this place.

– Oh, why, I ask her, – I think about how long I could not walk on Khreshchatyk, could not look at the poorly hidden burnt skeleton of the building of the Trade Unions. After the revolution, the Maidan remained a place of smoke and blood for me for almost four years, until I started working nearby and had to go to the Maidan Nezalezhnosti metro station every day.

She says:

– Only God knows how much money was spent on the reconstruction of this place!

I interrupt:

– Corruption?

– Yes, and that too. But they did not give this place back to the townspeople. It was a public library, and now they charge money for admission.

– How many?

– 5 euros.

– Seriously? Horrible!

– The premises were not given to the library either, although they were promised. Librarians have been huddling in other rooms for decades. There were talks about the construction of a new library, but no one has done anything. Only very rich people can rent a hall there for a wedding or celebration. Although who knows how many donations of foreign money, public money went to reconstruction. Glad you liked the inside. But I avoid it, if it weren’t for the presentation of the book, I would never have gone there.

The tourist guide costs the next one and a half euros, about which there is not a word on the poster.

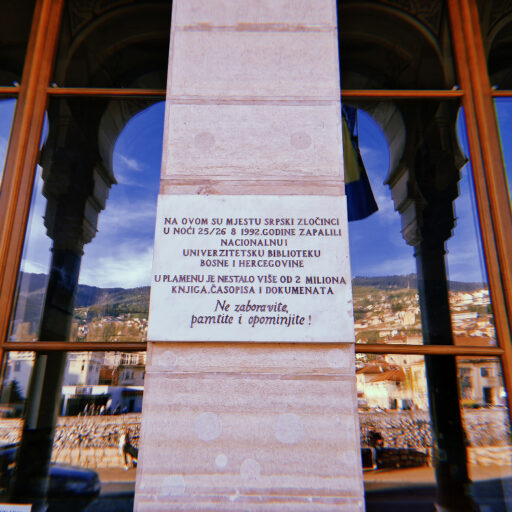

In the basement, there is a museum of the history of the town hall. The text bypasses who burned the library. The exhibition tells about the national library, about the year 72, and then – oh, the next hall with an imitation of a fire. Only one of the posters, dedicated to the war and the siege, mentions that “the library caught fire…” It is mentioned so impersonally as if the wrath of God ignited it.

At the entrance to the town hall, there is a sign that Serbian attackers burned down the library. How did the exhibition overlook it? But is this definition correct? “Why not the Serbian army, as determined by the court?” Velma asks. “Why not word it according to the tribunal’s opinion? Many Serbs were also under siege, it is not their fault.”

I think: “Was it done for peacekeeping purposes or in a shy erasure of history?”

On the first floor, around the corner from the restroom, is the Museum of the International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Around the stands with photos of war criminals, are the pictures of their victims. Mutilated bodies, skulls, and bones on full walls: photo wallpapers which are not for every taste – unlike birches with a forest near the lake. A woman in a working uniform walks past the room, hip-hop music plays loudly from her red belt bag.

I walk through an art exhibition on the top floor – the newest, conceptual art. Instead of Maryna Abramovych’s performance, there are big old non-working kinescope TVs.

At exactly 5:00 p.m., a security guard runs into the hall.

And confidently turns off the light on the floor.