Anastasiia Marushevska

Anastasiia Marushevska is a Ukrainian journalist, StratCom specialist, and public speaker. She serves as the Editor-in-Chief at the non-profit media Ukraïner International, overseeing the adaptation and creation of content related to Ukrainian culture, history, and social context in more than 10 languages. She is a co-founder and board member of the Ukrainian NGO PR Army, leading the project on the forcible deportation of Ukrainians to Russia titled “Where are our people?” as well as leading the research on the historical context of Russian crimes and propaganda.

About the Project

by Anastasiia Marushevska

“Memories in Chains. The Struggle for Closure in Prijedor” is a journalistic report that delves into the lingering trauma of the Bosnian War, focusing on the Prijedor region’s ethnic cleansing. Key topics include the personal losses and relentless pursuit of closure by survivors like activist Edin Ramulić, who lost his father and brother in a concentration camp. His brother is still officially missing, prompting Edin’s continuous search for missing persons and his brother’s remains. The report covers a trip around Prijedor, visiting former concentration camps Keraterm and Trnopolje, as well as mass graves and war cemeteries. During the journey, I discovered a Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and met the family of a Ukrainian priest living in Trnopolje who witnessed a wartime concentration camp there. I also found that a poem by Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko was used by Bosnian Serbs to justify their atrocities during the war.

The piece underscores the struggles in memorialising trauma amidst denial, poor reintegration efforts, and the loss of entire segments of society due to occupation, immigration in search of refuge, and forcible deportations by the aggressors. It highlights the ongoing relevance of these challenges for contemporary wars, such as the ongoing war in Ukraine. The detailed personal narratives and historical context emphasise the necessity of memory and justice in post-war societies.

Memories in Chains. The Struggle for Closure in Prijedor

The Bosnian War (6 April 1992 – 14 December 1995) ended almost 30 years ago. According to estimates, which, of course, are unlikely to be final, about 98,000 people died. Although the brutal armed conflict has subsided, for many survivors, the struggle continues. The search for missing persons and the trials of war criminals, most of whom still live close to their victims, are still ongoing.

“It was a place where your spirit was crushed”

In front of me stands a red and white building, a big dog chained in front of it walking lazily from side to side. A few cars are parked around, and the smell of paint, or maybe diesel, is almost overpowering. It looks like a set of garages or storage rooms, with a local “Bingo” supermarket attached to it and a Russian Gazprom station across the street.

We’re on the site of the former Keraterm concentration camp, the most notorious in the Prijedor region. It held mostly men of military age who were considered a threat by Bosnian Serbs. Prijedor became a part of Republika Srpska after the war, and most of its Bosniak inhabitants were deported and killed, fled, or are still missing since the beginning of war.

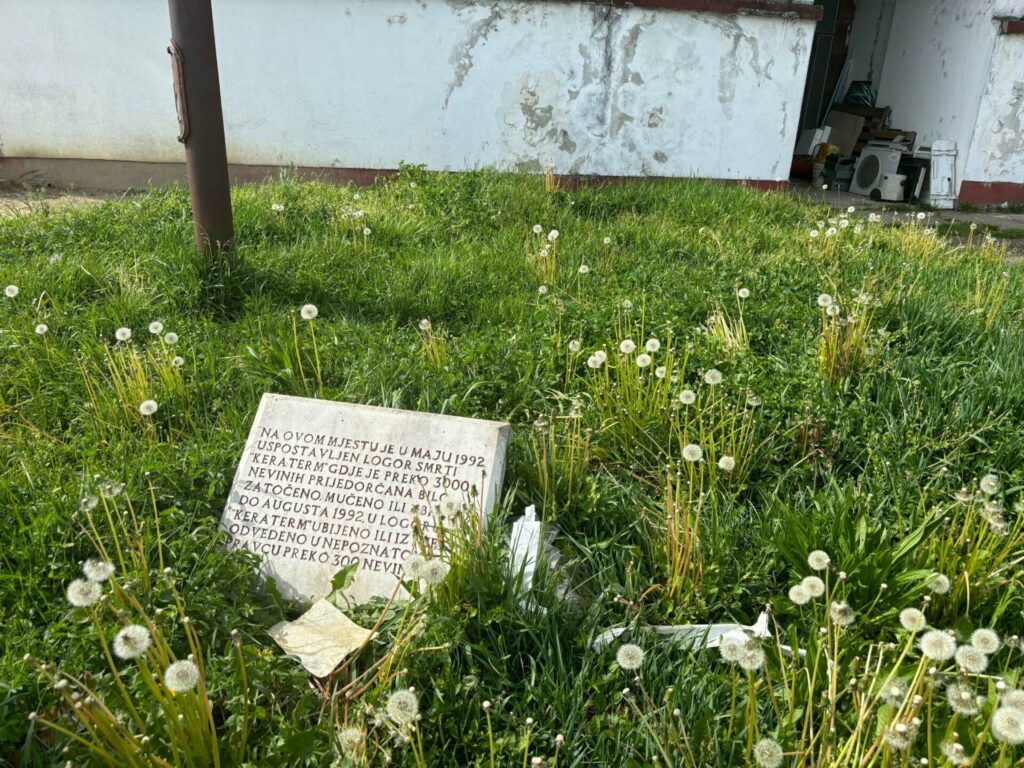

Stepping out of the car, I’m briefly disoriented until I see Edin Ramulić, my guide in the Prijedor area, clearing trash from the grass. Only now do I notice a modest plaque that reads (translated from Bosnian):

“In May 1992, the Keraterm death camp was established on this site, where more than 3,000 innocent Prijedorians were detained, tortured, or killed. By August 1992, 300 innocent people had been killed in the Keraterm camp or are still missing.”

It appears that Edin installed this plaque himself and was now cleaning, also himself. I’m awkwardly looking at him and start taking pictures, like the idea of trash on the memorial is that unusual. The tombstone is dedicated to the men killed in this camp, including Edin’s father and brother.

The red and white building has bullet holes in its walls, and as I approach to take photos, the chained dog gets upset, as if he is protecting them. The new owners of the building are trying to cover the holes with thick layers of paint, but it keeps peeling off. For Edin, these holes are painfully symbolic, as it was here that his father was shot along with over a hundred other prisoners. The victims were later buried in a mass grave in the neighbouring village of Tomašica. His brother is still officially missing – no remains have been found. The man who killed Edin’s father also lives in Prijedor. Sometimes, Edin sees him on the street or in the supermarket.

“It wasn’t simply a place for imprisoning people, but a place where your spirit was crushed,” says Edin about the Keraterm camp, sharing his story with me, a Hungarian archivist, and a Bosnian woman who now lives in Croatia. She helped translate but soon broke down in tears. Edin continued telling the story, unfazed by any reaction. “The level of dehumanisation was incomprehensible. During 12-hour shifts, perhaps out of boredom, guards would demand people fight each other, commit rape, and do all kinds of perverted things… They used every type of torture, except for electric shock, as they didn’t have electricity. The most striking thing is that it was done by neighbours to neighbours. Even ordinary citizens could come and ask a guard to punish people they knew.”

“For me, the search for missing people ends not at the grave, but at trial”

Edin is a well-known activist in the Prijedor region. Because of this, his name appears on numerous blacklists. His own list of names of unpunished criminals, radical nationalists, and people who are not interested in preserving the memory of the crimes and their victims is no less extensive. He is a champion for peace and human rights, but most of his work addresses the past he has personally witnessed. At 21, he experienced the attack on Prijedor and its surrounding villages by Bosnian Serbs, marking the beginning of the war that, for him, has never ended.

“In my life and work, I don’t feel it as much as I do when I see my mother. Every time I see her, I’m reminded of the problem – that I couldn’t find my brother. I feel a sense of responsibility and guilt, even though my mother has never said anything. I feel guilty because I didn’t share their last moments with them. But if for my mother, the search for missing people ends with bones, for me, it ends not at the grave, but at trial.”

Guilt drives Edin, compelling him to tirelessly search for his brother, for other missing persons, and for closure. It seems he remembers every name from the list of over 4,000 people from the Prijedor area who were either killed or are still considered missing. As we visit memorials in the village of Kozarac and in downtown Prijedor, Edin points out names on the memorial plates, sharing stories of the individuals. “He’s Muslim, they didn’t ask for permission to put his name here,” he remarks, or “this one is a Croat, that one a war criminal.”

In a Muslim cemetery, he suddenly stops at a tombstone dated 1992 and notices that the woman buried here was killed in the Trnopolje concentration camp. The strange thing is that even after her death, this woman turned out to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. This cemetery is divided into two parts: one for the general Muslim population and another for victims of the Bosnian War (many of whose remains were found later in mass graves). Thus, according to local logic, the woman buried under that tombstone should have been buried in a different area of the cemetery.

“If there was light, it meant that was a Serbian house”

On my second day in Prijedor, I go with my guide Edin and local activist Isidora to the former concentration camp in Trnopolje. It’s a village with a quite familiar name for me as a Ukrainian, as it sounds like the city of Ternopil in the west of Ukraine. Suddenly, my guide shouts out in broken English, “Ukrainian church!” and points off to the side of the road. I immediately look for an Orthodox church, because it would align with the faith of the local Serbs, who are also Orthodox. However, it turns out that it’s a Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. It appears that this village used to have a large Ukrainian community among a mostly Bosniak population, but it became known in history books for its concentration camp.

On the way to the former Trnopolje concentration camp, we take a detour to visit Mykhailo Stakhnyk, a local Greek Catholic priest. Upon arrival, we’re introduced to his bustling household: his wife, two of their seven children, a blur of three or four cats, three dogs, and a flock of poultry. Located next to a church and a Ukrainian cemetery, their home testifies to a life steeped in faith and community. The priest’s son, also named Mykhailo, effortlessly switches between languages – Ukrainian with me, Serbian with Edin and Isidora, and English with a Hungarian archivist. Around 30 years old, he exudes a maturity and hospitality that belie his years. A former music theory student who spent time in the U.S., he now anchors himself at the family homestead. He serves us homemade apple juice while his mother shares stories about the propaganda from Republika Srpska regarding modern Ukraine, which she describes as “unbearable to watch”. Her origins are from near Ternopil, and although their family ties to Ukraine are few, the entire family speaks Ukrainian and supports Ukraine. At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, they collected humanitarian aid, but it was difficult to send due to complications imposed by Republika Srpska.

The following day, I revisit the welcoming home of this Ukrainian family to talk to the priest. During my initial visit he was at a local school, dedicating his time to the children of the Ukrainian community and teaching them the Ukrainian language. Mykhailo gives me a tour of the church, tells me the history of Ukrainians in the region, and shares his memories of the Bosnian War.

According to him, the concentration camp wasn’t limited to just a few buildings, it took over the whole village. Guards would take women to empty houses and rape them, or take prisoners outside the camp’s official premises to murder them. One of the Serb guards killed almost a whole Ukrainian family. Only a young girl managed to escape.

“This region was developed; we had electricity and telephones. During the six months of the war, all of that disappeared – no electricity, no telephones, no running water. Before the war, if you went out and looked around [at night], everything glowed like corals. A few months into the war, it was just darkness. If there was light, it meant that was a Serbian house.”

Another local girl was randomly shot by one of the guards near the school. Why, no one knows. Children go to this school now, so Edin asks me to respect it and not take too many pictures. Instead, I photograph a blossoming tree and a metal sign with “Trnopolje” written in Serbian Cyrillic.

“We’re all patients, we’re all sick”

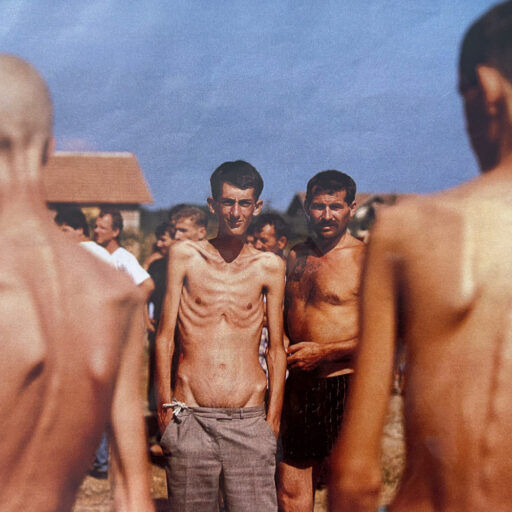

Edin walks around the former camp with his red folder, where pictures of the Trnopolje camp’s victims and survivors are carefully placed in plastic covers and shown at the appropriate moment. One of the photos is of Fikret Alić, a still image from a film that was on the cover of Time magazine in 1992, shocking the world.

We stand at the spot where the photo was taken and where my guide, Edin Ramulić, 21 years old at the time, was also held prisoner. Most of the survivors don’t speak much about their experiences, but Edin takes on the job for the thousands of voices that won’t be heard. He endured and survived nearly every aspect of the war – the ethnic cleansing of his village, the destruction of his home (which is yet to be rebuilt), the loss of his brother and father, being sent with his mother to the Trnopolje camp, managing to leave, and later serving as a soldier for the Bosnian army.

I spoke with Edin over several days at various poignant locations – former concentration camps, mass graves, and memorials – as well as in more private settings within his office. Edin’s methodical, almost professional approach to recounting war stories suggests he has narrated these tales countless times. Yet, none of these stories lose their significance. He delivers each of them with meticulous detail, embodying his roles as a participant, researcher, activist, and devoted resident of Prijedor. Each narrative remains deeply personal.

When I broach the subject of deportations and imprisonment in concentration camps, Edin shifts to his family’s story. He seems to still be surprised by the duplicity of the Bosnian Serbs, who were friends, neighbours, and colleagues shortly before the war and then came to separate families, take away property, and kill. He seems overcome with guilt when he says that he managed to escape not because of any extraordinary courage, as he sees it, but because of chance, while his father and brother did not.

“Bosnian Serbs surrounded villages and went from house to house, taking men to one type of camps. Then, either on the same day or a few days later, they would return to take the women and children to another camp,” explains Edin. “They transported people in large trucks, sometimes in buses. I was saved because I looked much younger than my age – I was 21 at the time. When the Serb army came, a soldier asked my age, and I told him the truth. He instructed me to go back to the other soldiers and say that I was 17. However, when my father showed the same soldier documents confirming his weak heart and his status as a patient, the soldier replied, ‘We’re all patients, we’re all sick.’”

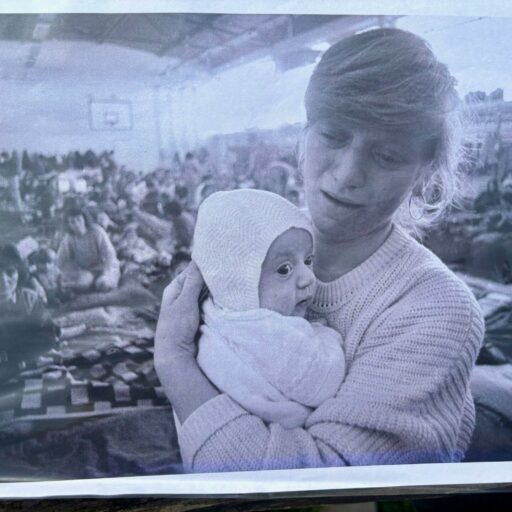

Edin and his mother were taken to the Trnopolje camp, where he stayed for several days and managed to leave by claiming he was a minor. This camp was known as the least horrific, with no systematic killings. It operated more as a stage for further deportations. Men mostly slept outdoors on the school football field, while women and children were held inside the buildings. Now, activists from the Kvart organisation (like Edin and Isidora) hold carpet performances called “Night in Trnopolje” on this field every year on 5 August. They spread colourful carpets and sit on them together with former prisoners, activists, and diaspora members, honouring the memory of the victims.

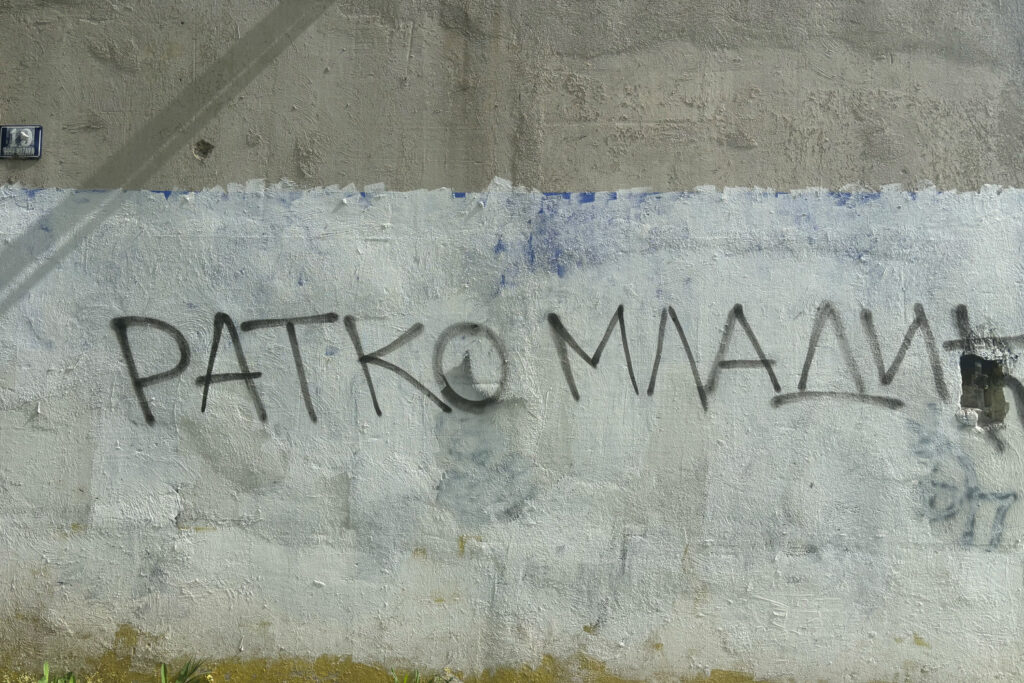

On the other side of the former concentration camp, however, there is a memorial dedicated not to the victims, but to the Serbian soldiers who tortured and killed them. Remarkably, this monument once featured an excerpt from Taras Shevchenko’s poem “Testament” alongside a piece by Petar Kočić, a Serbian and Bosnian poet. The Shevchenko excerpt goes like this:

“When I am dead, bury me…

Oh bury me, then rise ye up

And break your heavy chains

And water with the tyrants’ blood

The freedom you have gained.”

This pairing was likely an attempt by the Bosnian Serbs to lend a veneer of international legitimacy to their actions, perhaps hoping to appeal to the loyalty of the nearby Ukrainian community with Shevchenko’s verses. However, the plaque bearing the Ukrainian poem has since fallen off and was never replaced.

Concentration camps in the Prijedor region were initially discovered by international journalists. Radovan Karadzic, being a questionable strategist, invited reporters to see for themselves that there were no camps, only prisons for criminals. But the British ITN news team managed to film Trnopolje, capturing images of Fikret Alić and other inmates in dire conditions. These prisoners, transferred from Keraterm, suffered from dysentery, lice, and skin diseases. It was only later that the world learned that while the men were filmed outside, women and children were kept within the camp walls. After Trnopolje was revealed to the world, the men who had spoken to reporters, including Fikret Alić, were threatened. Alić eventually escaped by disguising himself as a woman. Later he wanted to join the Bosnian army, but he was coughing up blood.

Following the exposure of Trnopolje, the women and children were relocated to other regions of Bosnia or forced to leave the country. The men were sent to other camps, to Croatia, or faced death. The most notorious incident was the murder of about 200 men at Mount Vlasic, known as the Korićani Cliffs massacre, on August 21, 1992. This was after the international community already knew about the camps.

As a part of Karadzic’s propaganda campaign, the Bosnian Serb forces attempted a staged performance at Omarska, another death camp near Prijedor and the most well-known in the region. (Locals believe this is because it’s the only name Westerners can pronounce.) Karadzic showcased parts of Omarska to journalists with the artificial lavishness of a propagandist. Ed Vulliamy, one of the reporters who visited these camps and later testified in The Hague, noted that prisoners were too frightened to speak. The invitation also did not extend to visiting the “white house” where prisoners were tortured, raped, and killed. Edin often mentions Vulliamy, calling him “my best friend with whom I can’t speak”, referring to their different mother tongues. Now Omarska is a mine again, and people cannot just freely enter.

“They [Bosnian Serb forces] wanted to close the concentration camps quickly,” adds Edin. “On 5 August, the world learned about the Omarska camp, and by 6 August, they had moved prisoners from there to other camps. They were concerned that French diplomat Bernard Kouchner would visit Omarska after the journalists. Initially, the media played a key role.”

“They have never once attended a commemoration”

Driving around the surrounding villages, I see many beautiful houses built in various European styles, some resembling buildings from London’s Notting Hill. This creates an impression of wealth, suggesting a move from wartime living towards living in prosperity. However, the only issue is that these houses are empty. When the war ended, not everyone returned to live in their homeland, and the reasons vary. Some rebuilt their homes as a declaration to the Serbs that Bosniaks had not been eradicated from these lands. Others, still haunted by their experiences, cannot feel safe here. There are those who constructed houses for their children who, however, do not want to leave other European countries where they have already settled. Locals call all these people “diaspora”.

This situation highlights a significant problem: Bosnia has lost substantial segments of its society that could have become a civil force. Ethnic cleansing, deportations, population replacements, immigration, and nearly non-existent reintegration policies have created a social crisis.

While visiting a mass grave in Tomašica, where the bones of Edin’s father were found, we stop near an attractive house with two men relaxing outside. One is wearing a taqiyah; which seems to symbolise the Muslim holiday of Ramadan. The younger one has no obvious religious symbols, but he pours tea in the Turkish style, a tradition that probably dates back to the Ottoman Empire. Both greet us casually as we walk to the tombstone next to their house. I’m happy to see that the village isn’t deserted despite the presence of mass graves and graveyards right in the middle of it. However, Edin explains that it’s the end of Ramadan, known as Bayram in Bosnia, which is why more people are around.

He notes that the “diaspora” returns only for holidays, living in their beautiful houses perhaps just two weeks a year.

“I’m not sure that I share the same emotions as others who have lost someone. I know people who live in America and attend every football match where Bosnia is playing. They appreciate the representation of Bosnia, but they have never once attended a commemoration at the places where their parents were killed. I think they are lucky to have the opportunity to do that.”

The Prijedor region, part of Republika Srpska, offers a glimpse into the future challenges that any war-torn country might face. Rather than a memorial at the former Omarska camp, there is a mine; a small tombstone covered with trash marks Keraterm; and a monument glorifies Serbian forces instead of commemorating the victims at Trnopolje.

Discussing the preservation of memory and the struggle for justice in Republika Srpska is complex. The government is uncooperative with victims and even denies their rights. Activists are divided, with some gravitating towards nationalism and others striving to maintain rationality. Edin points out that corruption hinders progress, while other activists lament the “big politics” they claim to not be part of, despite operating in a highly politicised environment and undertaking roles that civil society should – co-governing a country.

After visiting the Prijedor district, I am still haunted by the very first thing I saw, that image of a dog chained in front of the former Keraterm camp, ignored by everyone. Perhaps it’s the effect of a first impression or Edin’s dedication to his family, who were killed there, that makes this place particularly poignant for me. Or maybe it’s the uneasy feeling that chained dogs always give me, as if time has frozen, and whatever improvements we make as humanity, we still fail. In Indonesia, where I’ve been living for the past 4 years, I see chained dogs frequently. I’ve seen them in Ukrainian villages and now in Bosnian villages too. People always have an explanation to help them sidestep responsibility: “It hunts our chickens”, “It runs onto the road”, “It bites people”. But I also understand that you can’t force someone to unchain their dog, as this is often tied to their worldview, their beliefs, and their fear of responsibility or judgement. Tethering an animal represents a type of evasive responsibility, reflecting an unwillingness to invest additional effort to reform the system. The issue lies not with the dog itself, but with our prevailing notions of how it should coexist with us in a domesticated environment. Changing this requires patience, like starting with vaccinations and sterilisation, gradually unchaining, and working towards complete freedom.

Since April 2022, when I first spoke with a man from Mariupol who, along with his wife, was taken to Russia, I have been gradually working to raise awareness that our people are being confined in camps, whether temporarily before deportation or indefinitely. The international community debates the correct terminology – whether to call it “abductions”, “kidnappings”, or “deportations” – while many Ukrainians are still in denial. The possibility that this issue could prolong the war for us for decades, especially if we’re forced to give up some of our territories, is sometimes dismissed. Most of those taken by Russian forces remain unaccounted for, not even officially recognized as missing or deported. They exist in a haunting limbo, trapped between their once peaceful lives in Ukraine, the threat of death, and the possibility of never being found.

The only chance they have is through the Edins of our world, who, day after day, continue searching, offering closure, and unchaining memories that we would rather not have.