Katerina Babkina

Kateryna Babkina is a Ukrainian poet, prose writer, columnist, screenwriter, and playwright. She has authored five poetry collections, including “Lights of Saint Elm” and “It Does Not Hurt,” as well as a novel, “Sonia,” and a novel in short stories, “My Grandfather Danced the Best.” Her two collections of stories, “Lilu After You” and “Happy Naked People,” along with four popular children’s books, showcase her versatility. Babkina’s works have been translated into numerous languages and her plays staged in Kyiv, Vienna, and Geneva.

Her translated works include “Sonia” in Polish, “Heute Fahre Ich nach Morgen” in German, and “Cappy and the Whale” by Penguin Random House. Babkina has contributed columns to Esquire Ukraine, Le Monde, and Harper’s Bazaar, with her poetry featured in various international anthologies.

Several short films based on her stories have been produced, with one screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 2016. She won the Angelus Central European Literature Award in 2021 for her novel published in Polish. In 2022, “Cappy and the Whale” was published in the UK, and in 2023, her novella “Mom, Do You Remember?” was released in Ukrainian.

Yet Another War Here: From Sarajevo to Kyiv

by Kateryna Babkina, April 2024

“All this has already happened–concentration camps, barracks, selections, ghettos, hideouts, hiding pursued people, armbands, piles of shoes left behind by the deceased, hunger, looting, knocking on the door in the middle of the night, disappearances from home, blood on the walls, destruction of homes, barns set on fire with people inside, pacification of villages, besieged cities, human shields, rape of women, the extermination of intellectuals, refugee columns, mass killings, mass graves, exhumations, international tribunals, missing persons,” writes Wojciech Tochman, the author of “Like Eating a Stone,” a book that tells the story of people who survived the Bosnian War and spent years afterward visiting the sites of mass grave exhumations, trying to find and bury at least a few bones of their parents, children, husbands, and wives.

Coming to Bosnia to be a part of the project, I was somewhat skeptical about this “Reporting from the Future” concept: Our wars, our times, and our contexts are so different. Yet, again and again, the people I’ve met–whether witnesses or survivors, soldiers or reporters who have covered and lived through dozens of wars and conflicts–repeated: “All this has already happened.”

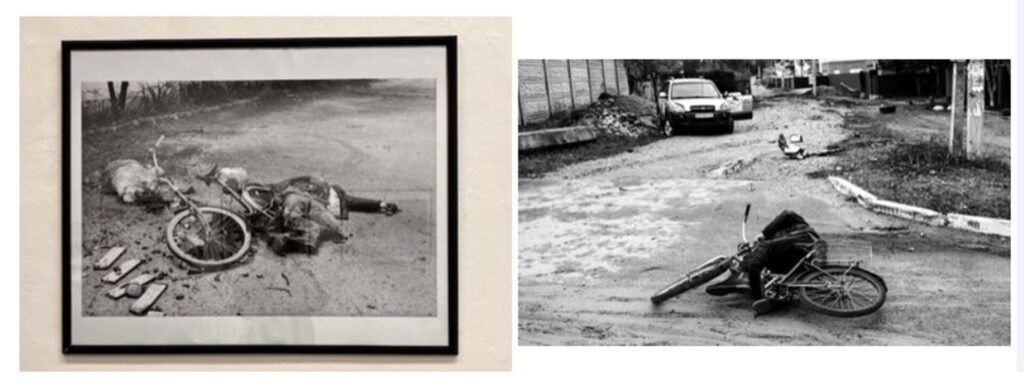

On my first evening in Sarajevo, I went to see the opening of the exhibition “Sarajevo: grad ljubavi i stradanja” (Sarajevo: the city of love and suffering), and already one of the first photos made me feel as if I’d seen it before. It was an image of a bicycle and a dead old civilian shot while crossing the village. After liberating the town of Bucha near Kyiv in the spring of 2022, someone had taken the same photo, and for a while, it was everywhere on the internet: a man, a bicycle, a death.

When I first arrived in Sarajevo, I’d seen a cherry tree by the Ali Pasha mosque that looked like a white and pink cloud. At the same time, Kyiv had burst out with cherry, apricot, and magnolia blossoms, which I saw everywhere on social media. On the night before I departed, the last petals were gone, taken by the wind around the small cemetery next to the mosque. The first green leaves had appeared on the cherry tree, though the surrounding mountains were still waiting, rocky and bare. But time moves so fast and brings such ultimate changes that, by the time I landed in London–where I had taken my toddler daughter from Ukraine in 2022 to keep her safe–the mountains were probably already all turning green, too.

Katya

“I feel such pity for my brother,” Katya says. “One bullet got into my lungs, so he saw me, leaning over him, with all that blood coming out from my throat.”

“You had 12 bullets in your body. Do you feel pity for yourself?” I ask.

“I fainted and did not see that, so that’s okay,” she laughs.

Katya is a nanny for my daughter when I have to travel with her. I first met her in Paris, where she was recommended to me by my friend, who’s a literary agent and has a lot of kids. She said Katya, now 18, was perfectly capable, and that was true. She dealt fantastically with my daughter and left the best impression. In fact, my daughter demanded we take her to live with us in London. I wouldn’t have minded, to be honest. If I had given birth when I was 20, Katya could have been my older daughter.

On March 5, 2022, when the Ukrainian town of Vorzel was already occupied by Russians, Katya’s family was trying to leave in their car after spending a couple of nights in their neighbor’s basement. They did not know precisely what was going on in the town, as they did not have electricity and there was no internet.

The car was stopped at a Russian checkpoint. A man holding a gun asked Katya’s father where he was going and what was in the car. “Dad answered that we were going away and that there were two kids in the car,” Katya says. “And the man said we could go. He was very close, less than 100 meters, and he could see who was in the car. When the car moved, he started shooting. Apparently, there were soldiers in every house on the street, and they started shooting too. One was even firing an automatic firearm–those bullets destroyed my leg–while the others shot with machine guns.”

Katya shielded her brother and her cat with her body, so her brother wasn’t shot at all. Katya and her mom were severely wounded, and her father got, as she says, “just one” bullet in his leg. The man who had told them they could go and then shot at them came to see what was inside the car and said, “Sister, I’m sorry, I thought you had guns in there or something.” Katya’s brother, 8 years old at the time, swore at him. The family was let go, and the father drove to the Bucha children’s hospital. Katya’s heart had stopped by the time they arrived, but despite the hospital itself being under attack at that very moment, they brought Katya back to life. So sometimes I call her a zombie, and she laughs.

After a couple of weeks in different hospitals, Katya and her mother were taken to Charite Hospital in Berlin. The whole family still lives in Berlin. Katya and her brother go to school, and Katya is also attending intensive German courses and works as a barista, hairdresser’s assistant, or babysitter. She’s the only one in the family who works.

She makes a lot of jokes about what happened to her and hates it when her new friends see the photograph of the Ukrainian president visiting her in the hospital and ask her to tell the story again and again. Not because she doesn’t want to talk about it, but because those who listen then cry or feel scared, and she prefers to make fun of it. As she puts it, the physical pain during the year of recovery was enough, so she never lets herself suffer about what happened to her or think about how awful it was.

Katya came with me to Sarajevo, and we talked a lot about the siege, the war, the memory, and the holes in the walls of almost every building left by mines or bullets. Katya wonders why they don’t repair the walls and if people are okay seeing those signs every day. I asked a couple of people, and mostly they say they don’t notice them anymore. Some say it’s important to remember, and only one person so far has told me it’s sick and depressing to be surrounded by those reminders of death all the time and he would prefer those signs to go. He spent all 1,425 days of the siege of Sarajevo right there as a soldier, and now from his window, he sees the training field of the Olympic stadium that was temporarily turned into a cemetery during the siege as they ran out of places to bury people.

This city is full of people like Katya–brave survivors, strong fighters, who make jokes and fun out of what happened to them. But there’s a lot underneath.

As for the cat, Katya’s father told her that when he opened the door to see what was happening with Katya and her mother, the cat ran away. But she says she doesn’t believe him.

Normal Things

In Sarajevo, I speak to women who were more or less Katya’s age during the war. These are the ones who would be considered lucky not to have any outstanding experience: They were not raped, tortured, or imprisoned, and their families survived. They did not have to roam the mountains, hungry and freezing, risking encounters with paramilitary Serbian units that were even more cruel and dangerous than the Chetniks. Just like Katya with that “just one” bullet in her father’s leg, they call “normal” the things that are far from normal or acceptable simply because Bosnia is full of far more awful stories.

Teenagers who were regularly gang raped by Serbian soldiers because they were Muslim, women who saw or heard their husbands, brothers, or fathers tortured or killed and mothers who lost young children and spent the years after the war looking for their bones at various exhumation sites–many of them still live everywhere around.

Maybe, in comparison to that, other things seem completely normal, especially 30 years later. Or maybe this is just a way to cope. The plank of normality is so easily lowered, and it does not rise again when things do, in fact, become more normal. What does war do to us? What are we ready to accept as normal after this?

One of the women, Leyla, says that during the war she did not care that there was no food or electricity in Sarajevo because life then was vivid. “In Grbavica, on the Serbian side of the city–it was scary there. No one was around. But in Sarajevo, we went to theater plays and there were a lot of kids to play with. We were outside all the time, enjoying ourselves. My father’s sister was just 10 years older than me and newly married; she and her husband took me out.”

Another woman, Narcisa, tells me that she and her friends were only allowed to stay in front of the building, but they went everywhere. When they went to a concert or other affairs, their main fear wasn’t bombings, grenades, or sniper bullets. Instead, they were in constantfear that their parents would notice they were not where they were supposed to be.

Just like in Ukraine now, there was an enormous surge of cultural and artistic life during the war in Sarajevo. They did not have electricity, paper, or film, let alone the internet, but that did not stop people from creating, studying, and organizing all kinds of exchanges. Just like in Ukraine now, people came to vist–not only journalists and reporters, documentarians and filmmakers, but artists, designers, writers, singers, actors, philosophers, as well. They did it to show solidarity and support, but they also did it to breathe in that special air so full of life, energy, and inspiration.

One of Narcisa’s friends was killed while sitting right next to her. They were playing cards when he just fell over. No one knew where the bullet had come from. Narcisa’s ex-husband was already a soldier back then and had lost his eye. When their kids were little, they used to ask where daddy’s eye was, and Narcisa and her husband would tell them, “Daddy went on a business trip and forgot his eye.”

Lejla, taken to Serbia for safety by her mother’s parents, who were also Serbs, witnessed a young Muslim woman, 18-20 years old, being taken away from the bus at a checkpoint and never coming back. All the people on the bus kept silent. Lejla herself was the daughter of a Muslim man who stayed in Sarajevo and fought. After two years away, when she was 14, she decided to find a way to return to Sarajevo, which was still under siege. She came up with the idea to keep a strict diet and lose weight so she would not be the only plump person in Sarajevo and make the others–who were suffering from malnutrition–feel bad, and she actually stuck to it.

As we talk, the list of those “quite normal things” they saw or experienced during the war grows and grows. Nothing they talk about is even close to normal.

Home

“My grandmother’s family in Vojvodina, Serbia, were very kind to me,” says Lejla. “I know a lot of people had this awful experience of being a refugee, but that was never the case for me. I was very welcomed there.” Later, talking about different things, she would say, “I was a very practical child. When we lived in Vojvodina, I knew we didn’t work and had no money of our own, so I couldn’t ask for things, like shoes or a bicycle.”

Both Lejla and Narcisa went back to Sarajevo during the siege. Narcisa’s family moved to Croatia before the war, but then returned to the town of Zenica in Bosnia and later came back into Sarajevo through the Tunnel of Hope, which was normally used to get out, and even that was not easy; humanitarian aid, weapons, and heavily wounded people were the priority.

Lejla was 14 and obsessed with getting back to her father and his family. During her stay in Serbia, they maybe spoke once or twice courtesy of radio amateurs from Sarajevo. Lejla was so preoccupied with thoughts of her father that sometimes her relatives would find her sitting, somnambulant, in the living room in the middle of the night, all dressed and packed. “I’m waiting for my dad,” she would say. “Did you forget he’s coming to pick me up?”

In 1993, when one of the bridges was opened and people from the part of Sarajevo under Serb control were allowed to visit their relatives or properties in the besieged zone, she and her grandparents went back to Grbavica and applied to cross the bridge. They would apply again and again. That was while she was keeping her strict diet. She was never allowed to cross, and at one point the organization responsible for those permits started expelling her and her grandmother from the building, yelling at them, “This is not happening!”

After months of waiting and despair, Lejla’s father sought help from his friend, the main man dealing with the exchange of prisoners of war. She never learned who they had to give back to the Serbs to get her to Sarajevo. She crossed the bridge on her birthday and lived under siege for more than a year.

Initial estimates placed the number of refugees and internally displaced people during the Bosnian War at 2.7 million, though later publications by the UN cite 2.2 million people. The exodus continued quite intensively after the war. In Ukraine, around 6 million people have been displaced, according to data assembled by the UN Refugee Agency. Roughly 32.2 million people left Ukraine, while 25.1 million have since returned to the country. People are returning to areas near the frontline, too.

I left Ukraine in March 2022 and I’m often asked if I’ll return and take my daughter back with me, and when. I don’t have an answer. I don’t even know how to approach this kind of decision. As we leave Sarajevo, I ask Katya if she wants to go back to Ukraine. She says she knows it’s better for her not to, but she thinks about going home all the time. Before the full-scale invasion, even at only 16, she had her plan to move to Kyiv and knew what job she would look for.

On the very same day as this conversation, Katya, after landing in Berlin, will go and spend part of her salary from Sarajevo to buy a kitten. Her father had forbidden her from doing so for two years, insisting it was totally irrational and irresponsible when they didn’t even have a home. But she decides that day that life is now, and that life without a cat sucks.