May God have a photograph of this

—Ilya Kaminsky, “Deaf Republic”

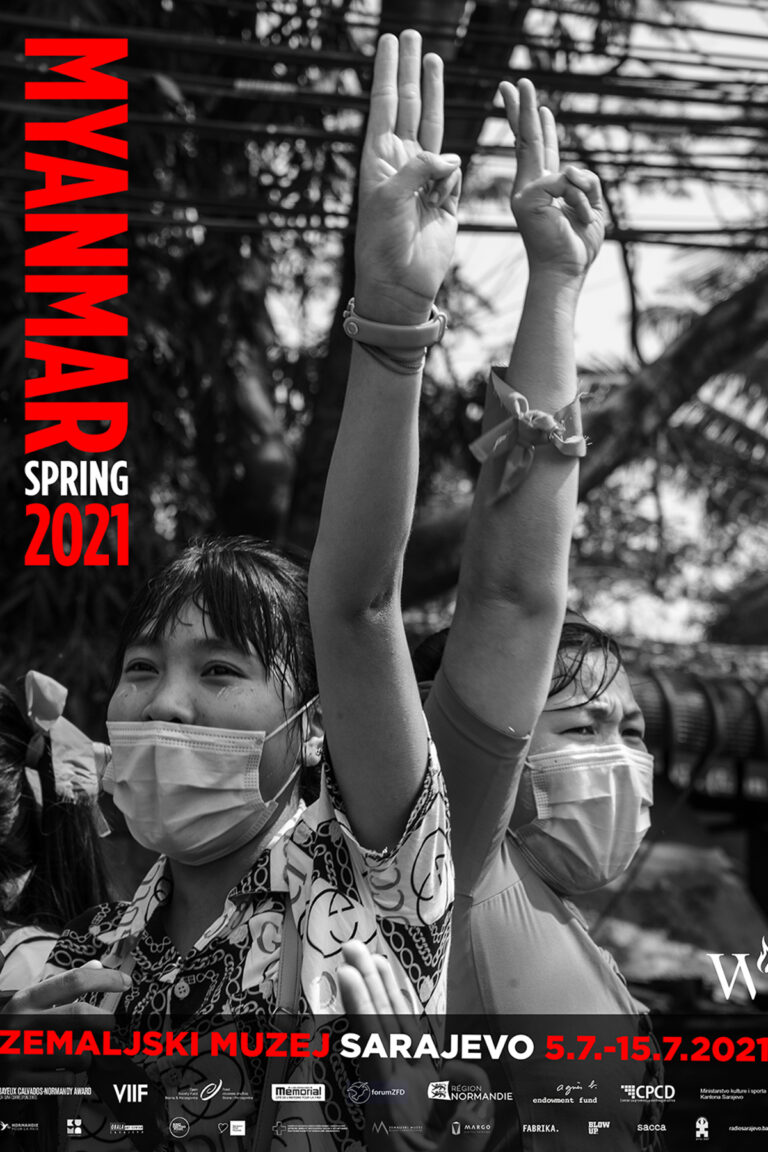

In the early days after the February coup, people still believed that peaceful protests could sway the hearts of soldiers.

They marched past the lofty tenements of Myanmar’s biggest city, Yangon, and through dusty towns and villages across the country. They denounced the coup and demanded the release of their elected leaders. There were thousands of them: doctors, teachers, students, bank clerks, bus drivers, civil servants, garbage collectors, poets. They called it the Spring Revolution.

Moving among them were photographers wearing vests and helmets bearing the word “PRESS.” For much of its modern history, Myanmar had been a military dictatorship that censored and jailed its journalists. But these young people had become photographers during an era of reform and were accustomed to operating with relative freedom. For them, “PRESS” was a badge of honour.

When the crackdown began, that badge became a target. The military and police tried to disperse the protesters with tear gas, stun grenades and rubber bullets. When that failed, they shot live rounds from assault rifles and machine guns, or picked off protesters with sniper fire. An orgy of killing began.

The photographers were also singled out. They were shot at, beaten and arrested. Soon, they stopped wearing anything that identified them as the press. Myanmar’s soldiers and police have now killed more than a thousand people. Dozens of victims were children, some of them shot in the head. Thousands more people languish in jail.

“May God have a photograph of this,” despairs Alfonso, a character in Kaminsky’s epic poem, as he watches soldiers drag a murdered boy through the streets of an imaginary dictatorship where photographers don’t seem to exist. Thanks to the bravery of our youthful exhibitors, we have many photographs of real-life atrocities in Myanmar. “My heart is broken,” says one photographer, “but I will never stop taking photos.”

Others of his generation have joined armed militias to launch attacks against soldiers and police. Myanmar’s cities are routinely rocked by bombings and fighting escalates in its ethnic borderlands. The health system is collapsing amid a pandemic. The economy is in freefall.

Yet hope endures. To this day, there are protests – small and sporadic, but protests nonetheless. In a complex country where people of different religions and ethnicities have fought and killed each other, the coup has unified the nation around a common enemy, the military. Myanmar’s Spring is over. A long, dark winter has begun.

***