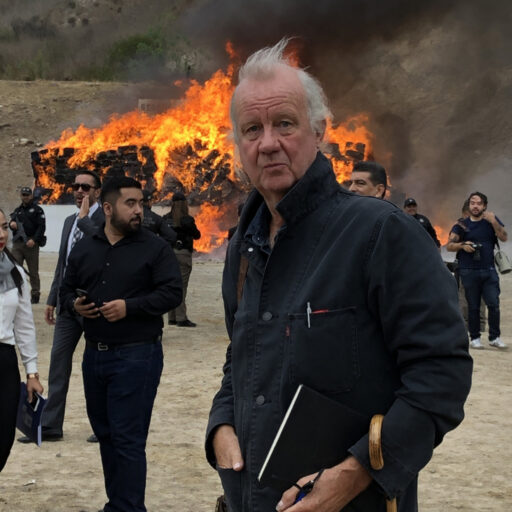

Ed Vulliamy

Journalist

On Handwriting

by Ed Vulliamy

Sarajevo, 7.7.2025

Earlier this year, the writer Christine Rosen contributed an article to The Guardian’s Long Read section on handwriting. Not just the physical act of writing with a pen or pencil, but its cognitive process and importance. Rosen explores the unthinkable notion that human beings are ceasing to do something they have done since soon after they stood up and walked on two legs hundreds of thousands years ago: WRITE. Something utterly primal to our existence: write on cave walls, carve into stone, ink onto animal skins, parchment and eventually paper. And Rosen explores the cognitive implications of this demise: in essence, that the end of writing sends evolution (if one believes the fantasy of humanity’s ‘progress’) into reverse: the less we write, with writing instruments onto a surface, not a screen, the more stupid we become.

The article was like the twin to another, in The Atlantic magazine last year by Rose Horowitch, about how even some students of literature at America’s elite Ivy League universities – let alone many other people – now struggle to read a full-length novel.

What we present here is part of Rosen’s argument. These are notes gathered during our research as journalists, not prose on a page for publication, but we are not showing you cabinets full of laptops, tape-recorders and i-phones. We present the raw material that means most to us as we go about gathering testimony and try to convey the world: our notes. Written in pen and pencil, onto pages between the covers of that greatest piece of technology of them all: the book. This time, books with blank pages, that we fill with observations, quotes, descriptions, attempts to verbalise reality. An urge as old as language.

At its best, journalism is visceral, and there is something elemental – almost primal – about a notebook full of hand- writing. Ideally, shorthand, because shorthand is an authentic record – no one can write longhand at the speed of speech. A longhand note is by definition a summary, not a quote.

Journalism at its best is testimony of some kind, and you cannot handle testimony on your laptop, let alone your mobile phone, in the same way as you can in a notebook. It’s like the difference between a vinyl LP record and Spotify. Notebooks exist; their system will not ‘crash,’ their signal will not cut out, their battery will not run down; you’ll need another notebook, but not a power bank. Your ‘record’ button cannot stall or fail. At the end of the interview, or long stare out of a window, or along a ribbon of asphalt: there it is, on the page in your hands. Here, we deal in words on paper, not babble into the ether.

It is my contention, for what it is worth, that notebooks are not only quintes- sential to the trade, in a way that the ‘record button’ is not, but also demon- strate that what we see and hear matters to us, and we think it should matter to you too. Our notes set people in a context that matters: your phone cannot record the way you observe detail, light, smell, possessions in a room, a facial expression. Notebooks demonstrate that we record what we see and hear in good faith, and that these things are there in tangible, physical form for whatever purpose might serve the greater good. (In my case, even presentation to a court of law, if necessary. The notebook I offer is that I filled on the day I entered the Omarska and Trnopolje concentration camps in this country. Little thinking that they would one day become evidence for the prosecution in eight out of nine trials in which I testified for the war crimes tribunal in the Hague).

The transition from paper to digital technology has not been a sudden one. For a while, we took notes in these books, but wrote up our stories on typewriters, in an office. When my generation set out in this business, newspaper offices were deafening places: the clatter-clatter of Olivetti and Underwood machines. Then these marvellous contraptions be- came electric, with IBM’s so-called ‘golf-ball’ typewriters, and already the time between brain and paper was accelerated, the cognitive micro-sec- onds that might extend the thought, or find a better word, reduced.

Sometimes, we’d have our typewriter in a hotel room, for conveyance of the article by fax. Or correspondents sent stories by telex – I remember a machine in Bucharest during the supposed ‘revolution’ of winter 1989 with half the keys missing – you had to know which letter was where, and developed a guitarist’s leather fingertips. Covering the war in this country and others, however, a story would be written longhand in the same notebook as its gathering, which would then be driven up to 13 hours along mud tracks behind the front lines from, in my case, Travnik to the nearest PTT landline phone (in my case, Imotski, in Croatia), and from there dictated, word by word, some- times letter by letter to ‘copytakers’ back at base: “Yes, that’s Karadžić: K-A-R-A-D-Ž-I-Ž… Point. Paragraph…” Then one would pay for the call-in cash, as per the time it took, and drive back to Central Bosnia, job done, in order to fill another notebook and do it all again.

I’m not saying that the journalism was better than what is coming out of Ukraine now from one electronic device to another, and in Gaza, electronics are of course the only way the story can be told. But a notebook is more visceral, and for that, not something that belongs only to the past. Among the books you’ll see here is that filled by Jon Lee Anderson for The New Yorker, from his visit to the newly liberated Sednaya prison and death-camp in Damascus, just weeks ago, for one of the most unforgettable pieces of journalism in recent years.

Why is it different? What does it feel more visceral? Why does the sight of The Brothers Karamazov handwritten onto a pile of paper at the Dostoyevsky Museum in St. Petersburg send a shiver down the spine, quite apart from its contents?

I remain convinced that while some people have other addictions, obses- sions or pornographies, journalists and writers are excited by stationery. There is no place on earth wherein a journalist or writer is happier than in a good stationery store. The London Graphic Centre is the most dangerous place on earth for my credit card balance. The dictionary term for this condition is papyrophilia. When I was president of the jury for the Prix Bayeux – the Oscars of war report- ing held annually in Normandy – I insisted that we debate three new categories: best notebook, best pencil, best pen. The elite of combat journalism of course engages in lively debate over the best written article, best radio broadcast, best TV news piece, etc. etc. But this level of en- gagement is nothing compared to the passionate exchanges on behalf of Leuchtturm vs. Molsekine, Blackwing vs. Staedtler, or Parker vs. Muji. It was very funny, and self-deprecating – yet not. We care about this stuff, and we care about it with primal intensity. There is a level at which your note- book has to deserve the story – and vice versa: the story has to be worthy of your notebook, pencil or pen.

Every generation thinks it is witness- ing the end of something, and mine might just be right when it comes to the inversion of what Hannah Arendt (referring to the trial of Adolf Eichmann) called “the banality of evil” to what pertains in politics – and journalism – these days: the evil of banality. And, related to that, in lamenting the end of worthwhile and widespread handwriting on paper; the dying days of writing of letters for mailing by post, to make way for the banalities of social media ‘posts,’ and digital communication, even sloppy email. Witnessing the death throes of vocabulary and lexicon as expounded in Roget’s Thesaurus in favour of infantile text messages – ‘hi… lol… wtf?’ – ‘emojis’ and grunted dialogue; the dying of mindful thought on paper, and rise of the mindless tyranny by telephone and computer screen. The age of cerebral sloth.

But not entirely: there is a rebellion against the digital counter-revolution, among intelligent youth, frustrated with technology’s insult to its integ- rity, and lately the monstrosity of ‘Artificial Intelligence’ – technology’s latest oxymoron. This is an avant-gar- de, for sure, a revolutionary elite. But was there ever a revolution that did not spawn this way? It is happening: why else would ‘keeping a journal’ be back in fashion? Why else would high street and even airport stores be re- plete with ever-increasing, impressive ranges of notebooks in all sizes and colours? Why else would innovative Milanesi revive a defunct American idea – John Steinbeck’s Moleskine – and relaunch it with such success that it came to be challenged (and, arguably, superseded) by revived Leuchtturm, Clairefontaine, Rhodia, Lamy… There are not enough oldies like us to fuel such a market: this is you, reclaiming your individual articu- lacy from a global technoligarchy, and asserting your creativity against the sterility of cyberspace – by filling your notebooks with handwriting.

This is what we try to demonstrate here. With a journalistic twist. We humbly present heritage as reporters, as done on paper. Just as our printed newspapers and magazines are the technological descendants of William Caxton and the Gutenberg Bible, so these books are – at risk of sounding pretentiously ridiculous – offspring of humankind’s first attempts to describe what it saw onto a surface, in signs and hieroglyphics, thereafter language. As such, they are not relics, they are alive.