Zérane S. Girardeau

Zérane Confluence Artistique

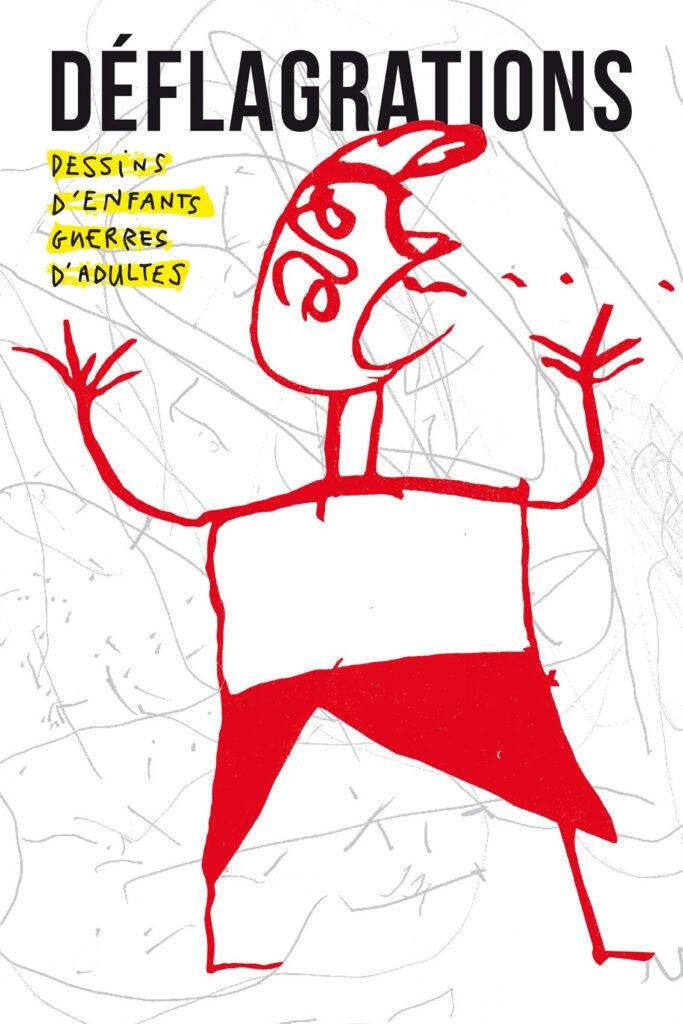

Déflagrations

Deflagrations is a journey through different lands and times signposted by drawings made by children who have been witnesses, victims and sometimes protagonists of wars, conflicts and mass crimes from 1914 to the present day.

These visual representations – a form of expression which is both universal and profoundly personal – depict traumatic experiences, cultures of war and of resistance, life and death, terror and dreams, weapons, fire, bodies, and also sun, trees, animals…

Confronting with our own eyes the visual traces left by children plunged into mass violence is the first step in arriving at an understanding of their full-on experiences and in recognising their individual memories and voices. Exhibiting these traces is both a duty and a tribute to these children’s acts of self-expression.

The exhibition features over 200 drawings made by children. This diverse body of work encompasses more than thirty wars and sketches out both personal and shared themes from a communal pool of individual experiences. Museums, national libraries, international institutions, NGOs, associations large and small, publishers, doctors, psychologists, war correspondents and artists have all played their part in preserving these drawings for posterity (albeit in the form of reproductions, as most of the originals are no longer extant).

In the light of the children’s tendency to share their drawings (an act that often initiates a personal conversation), artists, intellectuals and writers have sought to offer a response to these drawings. In the exhibition, their artworks, texts and reflections have been paired up with the children’s drawings.

Participating alongside Françoise Héritier and Enki Bilal in this exhibition are Laura Alcoba, Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane Blanquet, Patrick Chauvel, Monique Chemillier-Gendreau, Boubacar Boris Diop, Ernest Pignon-Ernest, Miguel Angel Estrella, Himat, Catherine Lalumière, Linda Lê, Erri de Luca, Mona Luison, Marie Rose Moro, Mohamad Omran, Remy Ourdan, Leïla Sebbar, Antonio Segui, Vladimir Velickovic, Léonard Vincent, Sonia Wieder-Atherton, Jérôme Zonder.

DEFLAGRATIONS

By Zérane S. Girardeau

The book Deflagrations, and the exhibition which inspired it, are a journey through different continents and times signposted by drawings made by children who have been witnesses, victims and sometimes protagonists of wars, conflicts and mass crimes on a massive scale from 1914 to the present day. Deflagrations depicts war from a child’s eye perspective in that universal yet profoundly personal language of visual representation, giving expression to traumatic experiences, cultures of war and resistance, terror and death, dreams and life, weapons and sun, trees… However intimate and unique they may be, all the more so given the wide variety of historical contexts depicted, these pictorial ‘traces’ created by the children reveal almost naturally a communality of experiences with visual and anthropological constants, as if these lines and colours expressed a solidarity among these ‘shaken souls’, in the words of Jan Patočka − ‘those who have experienced the shock’ and who remain ‘shaken in their faith in the daylight, life and peace’.

This book is a tribute to the children’s act of drawing – an act of play, of personal storytelling, of bonding and of healing. The persistence of life remains ever-present in their visual self-expression that becomes a means of resisting, of living and of reaching out to others. “These children weren’t drawing to please, but rather to connect: ‘bridge drawings’ between their past and present, and between the world of the dead and the world of the living. […] ‘Bridge drawings’ that for these children become ‘pathway drawings’ setting them on the path from inconsolable grief to recovery,’ wrote Serge Baqué after returning from a mission in the wake of the Rwandan genocide.

Deflagrations gives pride of place to the self-expression of these children, who have experienced mass violence full-on and who have a voice and a memory of their own which is quite distinct. The failure of society to recognise this voice has for a long time contributed to children being the forgotten ones of history. And yet… They are wounded, mutilated, tortured, killed, obliged to flee and forced to enlist, having only ever known a society at war. They are subjected to deprivation and to the spectacle of their loved ones suffering or dying. Confronting with our own eyes the traces they have left us is a path to realisation and recognition. Perhaps it is simply a duty on us, and the very least in terms of commitment and human dignity that we owe to these children who have been plunged into a maelstrom of violence and cruelty. Such an effort on our part requires us to efface ourselves: it is not for us to interpret their drawings or to bear witness in their stead by using the drawings to illustrate concepts elaborated independently of them. And lastly, revisiting this ‘child’s eye perspective’ offers us a chance to step for a moment outside the constant stream of indiscriminate images washing over us. It offers a kind of antidote to the sluggishness of habit, which transmutes barbarity into background noise or a distant fiction… It is like stepping to one side so as to remain alert and not to forget or allow our emotions to become deadened.

These pages are full of clamours amid the noises of war; clamours which will disconcert us. They make us confront the physicality of bodies and the material reality of the weapons of war. In depicting the barbarity of the Guernicas of this world, whether forgotten or ongoing, they make it impossible for us to avert our gaze from the abysses of the human race. We are a long way away from the ‘live images’ that appear on our screens. The images here are frozen. Time is suspended. The memories are raw. These coloured and black on white images depict destruction and combat, fire from the sky, bullets, blood, orgies of violence, explosions, planes, death, bombs, exploding barrels, fear, machetes and terror. And amid all of this, life tries to go on, with all the scars left behind on the bodies and in the minds. Were they photographed or filmed, some of the scenes drawn by the children would be unbearable for us to look at, so shattered are the bodies depicted. But sometimes the drawing invites our gaze into a scene onto which the child’s memory has been superimposed and brings us into intimate contact with the most extreme forms of violence – the inhumanity deep within humanity. ‘I don’t believe in the incommunicable,’ said the writer Charlotte Delbo, and these drawings undeniably contribute to transforming the unrepresentable and unconscionable into something that can be imagined. If we are prepared to listen to, and acknowledge, these clamours are perhaps also glimmers that illuminate our awareness.

For in front of our eyes and in the present moment, millions of children are living through wars and massacres, and some have never known anything else but a society at war. Terrible passions and fears are forever resurfacing and feeding hate-filled nationalism, fanaticism and the stigmatising of scapegoats, while erecting all kinds of new walls and fences. And meanwhile, the professional purveyors of arms wage a jaw-dropping but quite unabashed international competition. The anonymity of lives and the abstraction of figures can deaden sensibilities. By contrast, the intimate experiences perceived (and heard) in these children’s drawings project us ‘into’ the world and a community of real living people with their own vulnerable and finite natures. Perhaps these experiences will remind us of our shared responsibility for each other and of that spirit of solidarity for the victims, be they close or far away, familiar or unknown to us. Perhaps they will inspire unflagging vigilance in us and a determination to resist discourses, and their associated ideologies, that construct an image of the enemy – those same ideological constructions which prefigured and even legitimised some of the most appalling acts of violence of the 20th century. The clamours of these children – and the powerful attachment to life and desire to survive despite everything that they express – confronts us with a challenge for humanity, and with the impossibility of ever giving up.

In the light of the children’s tendency to share their drawings (an act that often initiates a personal conversation), artists, intellectuals and writers have provided their own response to individual drawings, offering insights, echoes and recognition of these ‘traces’ that transcend time and place.

A WARM Partner Project