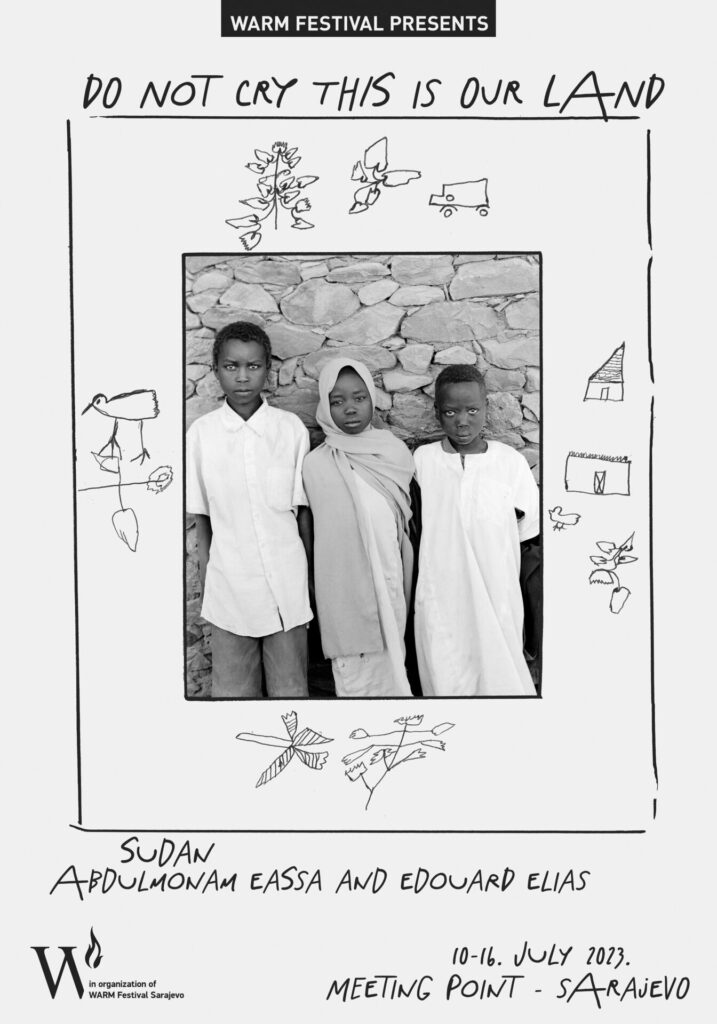

Edouard Elias

Photographer

Abdulmonam Eassa

Photographer

Do not cry, this is our land

Text: Eliott Brachet

Jebel Marra is an impregnable fortress. It is accessed through steep rocky paths on which donkeys are faster than cars. The first ravines through which overflowing rivers run in autumn give way to green highlands strewn with orange trees, apple trees and lemon trees surrounded by pine forests. The few thatch-roofed villages hanging on the volcanic rock that covers the highest peaks of Sudan, rising to over 3000 metres, can only be reached after several hours of walking.

Far from being a paradise, these mountains and their black earth still bear the scars of the war, of the bombardments by Antonov aircraft, gutted houses, caves carved into the mountainside, used as shelters for civilians fleeing the combat zones. Under siege since 2003, this mountain range located in the heart of Darfur, its backbone, is a pocket of resistance under the control of the Sudan Liberation Army, one of the last armed rebellions of the country that has never been dislodged by the central authority.

Twenty years after the conflict flared up, Darfur has not regained peace. All the attempts to silence the guns failed to solve the land conflicts, to allow the return of the nearly 3 million displaced to their lands and to do justice to the over 300,000 dead. In April 2019, the fall of Omar al-Bashir, wanted for “genocide” and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court, had given the population of Darfur a glimmer of hope. It seemed that a page was being turned. The UN peacekeepers withdrew. Peace agreements were signed in Juba in October 2020 between the authorities in the capital and several rebel groups.

The region is however still the scene of bloody clashes. In October 2021, the coup by a military close to al-Bashir’s regime did not help. The issue of land, of its distribution and of its coveted riches has not been solved yet. The right of return of the displaced is but a paper promise.

In Sudan, Abdulmonam Eassa and Edouard Elias travelled to the Jebel Marra mountains to meet with the Fur who found refuge there from the Janjawid militias’ abuses in December 2021.

They shot portraits and landscapes on black and white film with a field camera alongside the civilians and also their armed movement, the SLA (Sudan Liberation Army).

This four-handed work carried out by two photographers with a single camera combines several know-hows and soft skills.

Abdulmonam Eassa, a 27-year old photographer, moved to Khartoum in December 2020 to cover the news in Sudan, marked by a military coup in October 2021. He speaks Arabic, his native language, and he has been able, due to his human qualities, to develop a personal and professional network of contacts allowing him to understand events closely. Accompanied by Eliott Brachet, a freelance journalist, he has worked in many regions of Sudan.

Edouard Elias was less familiar with the region. This 31-year old photographer went to Sudan for several short stays before starting this project. He has provided his technical expertise regarding pre-digital field craft photography (10x12cm camera format), management of the photo developing chemicals and the films required for the project.

Two views and approaches have been necessary to complete this project, from its planning to the shooting, where the two photographers combined their sensitivities and eyes.

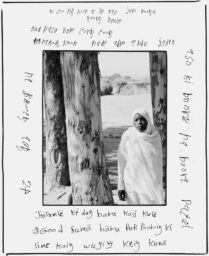

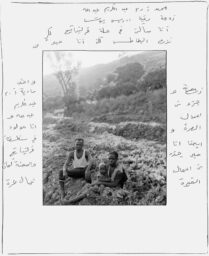

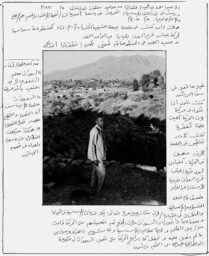

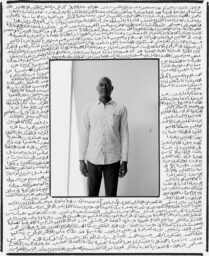

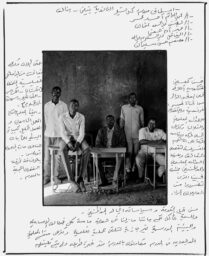

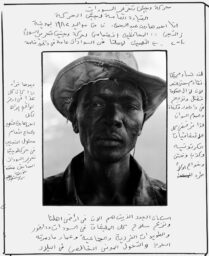

For each picture, the photographers asked the persons to pose in a familiar place so as to capture a moment in their daily life. After each shooting, a second picture was taken with an Instax instant camera (Polaroid) and given to them, whereupon each person photographed in Jebel Marra had the opportunity to handwrite what they wished about their life: their present, their past after years of war, or simply their hopes and their vision for the future.

Most of them wrote in Arabic, others in Fur dialect, and some, who could not write, dictated what they wished to convey. These texts are an integral part of the images, encompassing it. Thus, their words are whole and reproduced in their entirety. This method was designed to give them the opportunity to describe through their own eyes their self-image. Indeed, the photographer’s function is not only to freeze an image, to take it from those posing. The idea was to give a role to those accepting to go in front of the lens. They are then no longer subjects but players in their own photograph.

In the evening, in the starlight, the pictures were developed on the spot, then some were printed with an enlarger and given to the persons who had welcomed the two journalists and facilitated their work.

This work is the product of a close collaboration between the photographers and the photographed.